This is my second blog post on my research project, “Sight Unseen: Using creative methods to co-develop experiences of eruption at Volcán de Fuego, Guatemala”. The main aim of the project is to use creative methods to capture and explore older people’s memories of past eruptions of the active Fuego volcano in Guatemala. While my first post describes my process in making the zines, this post explores my original questions and eventual outcomes of the research, and the (mis)matches between the two.

In this post, I want to reflect on the original questions that motivated this research and the results that followed. These reflections are framed as a simple Q&A.

What was/were your original question(s)?

My original research question was:

- How can art be used to allow local people to explore memories of disaster and communicate these to others without direct experience?

I later revised this to two questions:

- (How) can visual arts be used as a tool for exploring experiences and memories of volcanic disaster?

- (How) can visual arts be used to engage a wider audience of policymakers, practitioners, and the general community to discuss and reflect on the impact and experience of volcanic disaster?

I revised my questions to reflect the diversity of participants I hoped to include in the participatory workshops. In fact, I think my original question already covered this!

Do you think your research has answered this question?

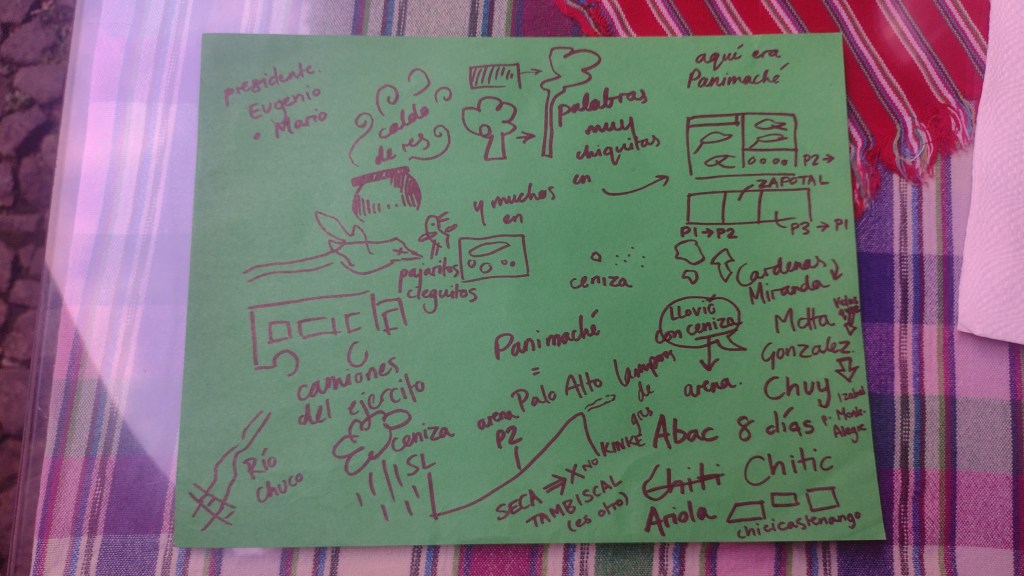

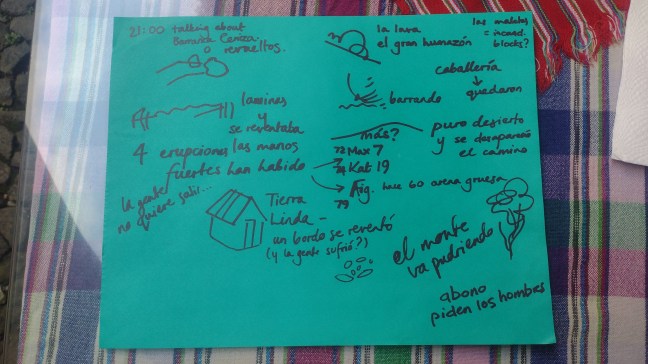

Yes, somewhat – particularly the question on how visual arts can be used as a tool for exploring memories of disaster. Early fieldwork on this theme was instructive: I made simple drawings about experiences of disaster that older people around Fuego had told me in interviews. When later I shared these drawings with these people and asked their responses, many expressed surprise and delight to see their stories represented. The drawings inspired conversations that elaborated on memories that the sketches portrayed. These were my favourite interactions: sharing my expression of the vivid memories that someone had told me seemed to represent a mutual desire to engage and be understood using different mediums (their voice, my art). It might also provide a tangible reminder of an event and suggest that a traumatic experience might nevertheless be worth preserving for the possibility of sharing the experiential knowledge contained within with others.

I was interested to find that in contrast to the overwhelmingly positive response to sketches and single drawings, people were sometimes mystified when (in subsequent fieldwork) I shared a zine with them. Perhaps a single drawing is a more explicit expression of that mutual desire to be understood between two individuals than a zine, which collects the experience of many thus is less personal? The zine may have inspired greater ambivalence for other reasons: could a zine be overwhelming in size and complexity for someone who’s never seen that kind of work before? Are there too many words for someone with limited literacy (true for many older people around Fuego)? Is there some cultural or emotional reticence involved?

It was difficult to answer my final question because the practitioners I had outlined in my proposal and invited were not able to attend the workshops. These were mostly for practical or logistical reasons. While it’s a pity not to have shed light on this, I think the question remains valid for potential future work!

What part of the project went well?

- Zine. I produced two versions of a zine that was narrated by people around Fuego and illustrated the experiences narrated. The second version included revisions and extra pages from interviews and a workshop in November 2022 intended to solicit feedback. I was very happy that the iterative process I had proposed in my grant application was somewhat successful here.

- Emotional response to the zine. I was deeply touched by some of the responses when I shared my illustrations with local people. Some replied in words (“That’s just it!”), and some showed it through faces and expressions. The zine resonated deeply with some people, which meant a huge deal to me after 6 years of working at Fuego.

- Emerging storytelling method? Through a women’s workshop (run by Teresa Armijos and Cristina Sala) and several interviews in November 2022, I started to develop an activity which involved an interview method where the participant used word and image excerpts from a cut-up zine in telling their personal experience of volcanic disaster. I think this activity has some potential as an eventual research method.

What part of the project was challenging? What could have gone better?

- “Esta historia no es de nosotros”. I was surprised to find just how specifically people wanted their stories told. Some people whose words I illustrated said, “This is great! But you know, I have many more of these stories that should appear”. Others said, “This story is not ours”. These people said it was their neighbours’, their siblings’, their partners’ – but that it did not apply to or resonate with them. This is both valid and an interesting counterpoint to the perspectives that inspired my grant application, where many local people expressed a desire to see their stories and those of their neighbours represented. I think this question – of how people are and/or want to be represented in disaster narratives – deserves a lot more thought, particularly from me!

- Drawings too good? The flipside to peoples’ positive reactions to my drawings was that sometimes people were more expansive when responding to a sketch than to a fully-developed illustration.

- Time required. It is very time-consuming to illustrate a book based on existing research and then revise it with feedback from its narrators. My fieldwork windows were November 2022 and March 2023. In that four-month window, I had to compile and document data I’d collected, reflect on and analyse findings, produce further illustrations, and plan for my second field season. This would be a lot even without my other work commitments! While it was a fantastic project, I would have to design a less time-intensive method in future.

- The tension between artist and researcher. This research was inspired by projects like “After Maria”, a collaboration between an academic, Dr. Gemma Sou, and an artist, John Cei Douglas. My project differs in that I am both the academic and the artist. This is a rare and fortunate opportunity, but it comes with distinct challenges! I have different standards for my art as an artist than I do as a researcher. As an artist, I want to make beautiful work in which colour, form, and emotion are paramount. This work is an expression of myself, my worldview, and my experiences of a landscape. I have a high standard for what makes a piece of my art “satisfying” to me. In contrast, as a researcher, my standard for art is that at which the art is useful for answering research questions – i.e., encourage a research participant to share more memories of their experience. In several cases at Fuego, this standard was a simple sketch. Throughout this project, I discovered an internal tension between the art I wanted to make as a researcher and the art I wanted to make as an artist.

How might you take this research forwards? What would you do differently?

I would ease the tension between the artist/researcher roles by separating the zine I made from the participatory activities I led during fieldwork. The zine represents a tangible research product which might be shared outside the community, while the activities hold promise as future research methods:

- Zine: the zines received great feedback from people who were unfamiliar with the legacy of 20th century eruptions of Fuego on livelihoods and landscape. They hold promise as a tangible research product which shares stories of disaster beyond the community that lived through it. With the permission of those who narrated the stories, there is potential here to disseminate the zine more widely.

- Research method: accept a more realistic art standard in exchange for more interactive research. I could develop participatory activities into a livescribing/storytelling method. With this method, I would invite either individuals or groups of 2-3 people to participate. I would have pieces of words and artwork that participants would be invited to sift through. Participants would be invited to use these in recounting their experiences in semi-structured interview, while I would direct the conversation and scribe on a big sheet of paper. The outcome of that interview would be illustrated on the sheet of paper and recorded on interview, and would be co-developed by myself and the participant.

What is feasible to do?

An important question! The two steps above are feasible with good planning and a more generous timeframe. While this work is very time-consuming, it is also deeply enriching.

This research was made possible by funding from the University of Bristol’s Arts and Humanities Research Council Impact Accelerator Account (AHRC IAA) in 2022 – 2025, specifically the Seed Funding account. I am hugely grateful for their support of me and my evolving research ideas. I have found this small grant invaluable in developing my profile as an independent researcher.

One thought on “Sight Unseen: responses and interactions”